What I learned while Vlarping

Moonrise Larp’s approach to larp is very clearly rooted in its founder’s theatrical experience.

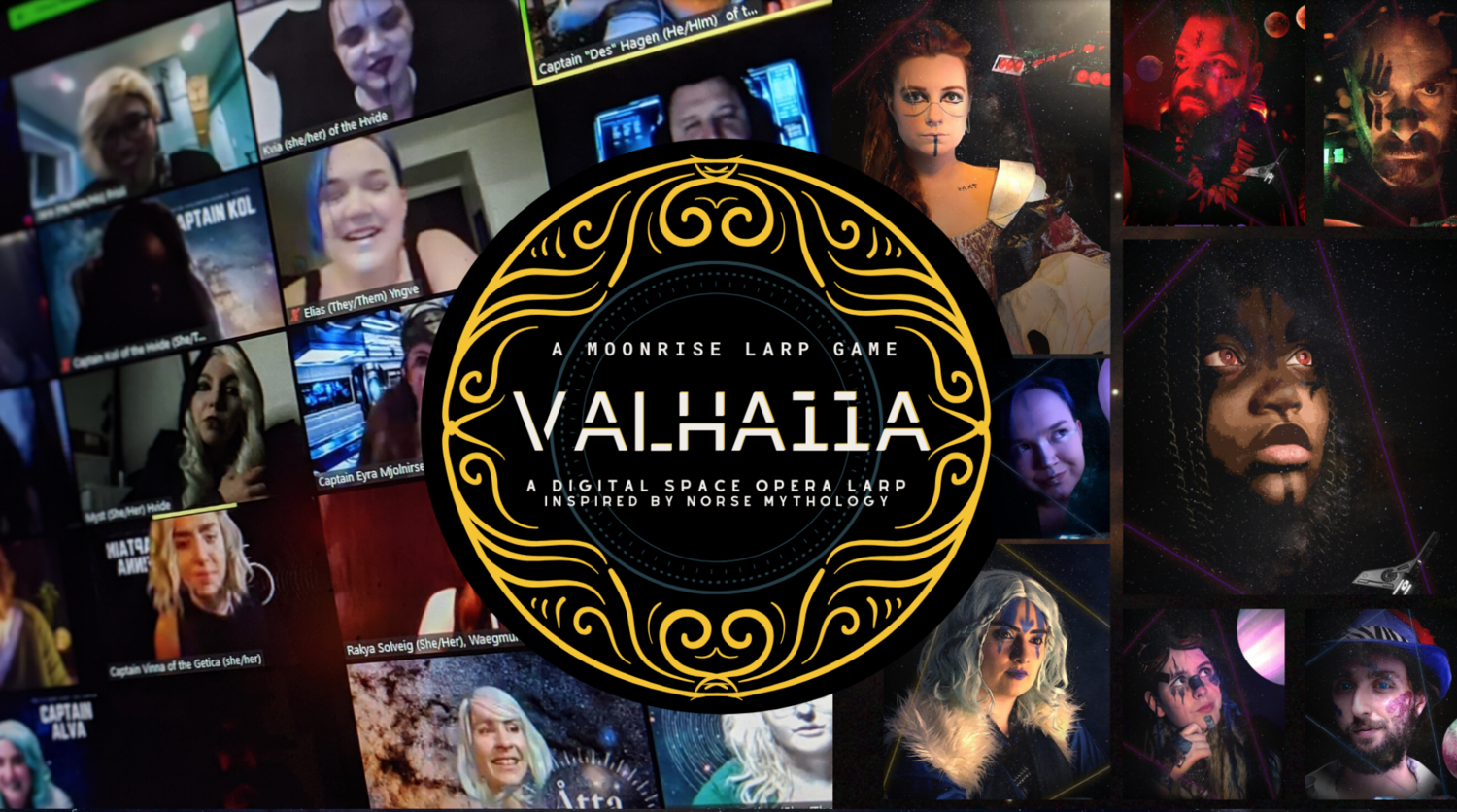

The six ships, each defined by ship ability and culture, determined our factions. And each ship was manned by a crew of players and two NPCs—the Captain and the ship’s Oracle, an AI system.

We had “rehearsals”; the NPC ensemble met twice weekly, and we outlined the events of each three-hour game into five “Acts,” following what felt like Freytag’s dramatic arc structure. Then, on Wednesdays, we met with the players to play weekly episodes together, over Zoom.

Although players fully embodied their characters through live action role-play, our togetherness was mediated through our computer screens. Our interactions did not exist where I sat, at home in Colorado, or where Moonrise Larp is located in Chicago; they unfolded in between, in the virtual realm of Zoom. And so we Virtually-larped together, from all throughout the United States and Canada. We… Vlarped.

The format of episodes with five acts limited player agency in a way that I felt was disappointing. For example, if my ship—the Yngve—was supposed to meet with Captain Kol’s crew aboard the Hvide, that meant that Captain Des and my character, Åtta, needed to manipulate our ship’s crew into navigating to a certain place at a certain time, whereupon Tiffany, the game master, would put our crew and the Hvide’s in the same Zoom room. If our ship’s players were mid-conversation or mid-puzzle when they were suddenly pulled into a room with the Hvide’s ship, the game would feel interrupted, and we as NPCs would have to smooth over the transition. This meant that players’ desires were sometimes put on the back burner, so that NPCs could better facilitate the predetermined events.

As a larper, it was infuriating. However, I understand.

In larp, if my character wants to speak to someone from another faction, I simply navigate my body through space to find that person whenever I want to. In past larps, this has meant I’ve wandered through woods for up to an hour seeking someone out prior to giving up, delivering messages to other members of their faction instead, or engaging in other interactions. However, when 40-50 folks are divided into different Zoom rooms, if one person suddenly desires to speak to someone aboard another “ship,” this requires quite a bit of logistical finagling on behalf of the game master, who is hosting the entire Zoom meeting (game). The narrative framework of each faction being on our own spaceship navigating the quadrants of space also limit individual agency of movement in the game.

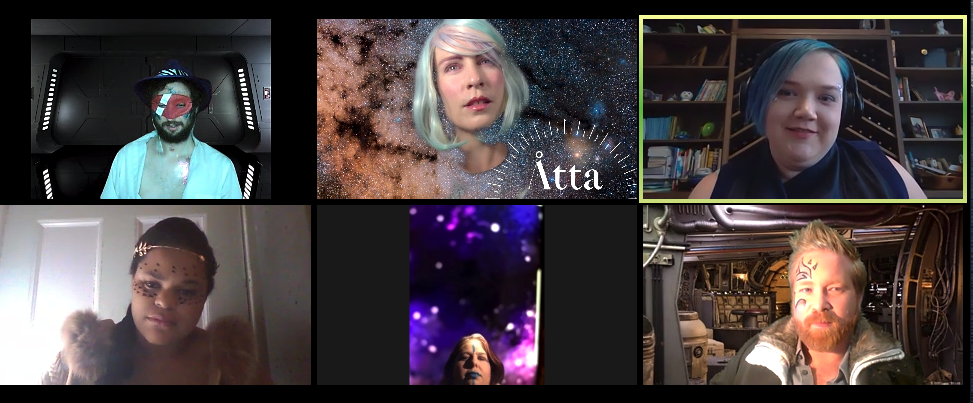

Even aboard one ship, player agency is somewhat limited. Zoom, by its nature, selects one microphone’s input to be heard at a time, which makes cross-conversation difficult. And our recent enculturation with Zoom meetings for work has trained many of us to listen somewhat passively when on Zoom calls. Overcoming this to engage players in the larp was not easy. My ship, the Yngve, had a crew of six, including Captain Des and Åtta, the NPCs. Captain Des often dominated conversations, and as an NPC team I would often remind him to ask questions and offer wait time to encourage our players to participate. In the midst of one game, watching an extended back-and-forth between Des and one player, I initiated conversation with another player through the chat window, which allowed two conversations to happen simultaneously. Because my character was an AI, we determined that we were conversing while their character, Eli, was using the Oracle interface, so communicating through the chat made sense within the lore of the world.

Reporting back to the NPC ensemble about this at our next “rehearsal”, all of the other Oracle NPCs decided that they would do this, too. It seemed that interaction was lacking on all of the ships, not just ours, and NPCs wanted more ways to engage players. I’m sure that the players felt limited by the Zoom structure, as well, and wished that the platform fostered greater player agency within the game. After all, player agency is a definitive characteristic of larp, separating larp from other forms of immersive performance.

After a few games, we found more ways to engage players. Tiffany swore that all of our players were enjoying themselves, and when we wrapped the show, player feedback clamored for a “season 2”. So, we’re planning that now, looking for more ways to keep higher amounts of people simultaneously engaged.

The consent mechanics that I created worked—when they were implemented. Three players from my ship wrote in their feedback forms that they appreciated the frequent check-ins, and one player in particular stated that the NPC’s use of check-ins made her feel capable of letting us know when a topic came up that was related to her personal trauma and needed to be avoided. However, as one of my players put it, “there wasn’t a consent-concerned NPC on every ship.” Players on other ships reported that their crews never used check-ins, and one player reported that another character relentlessly pursued her character romantically in a way that made her, as a player, uncomfortable, and she hadn’t known what to do to stop the behavior. I suspect that this may be due, in large part, to the fact that NPCs were never trained regarding consent mechanics, and players attended one short onboarding session prior to the first game, but the mechanics were never reviewed. Therefore, the awareness and culture of NPCs and players aboard any given ship greatly influenced whether the mechanics were used. There was no game-wide consent culture established. These mechanics did not become an enculturated language or normalized tool for communication throughout the player base or NPC ensemble. Without the reinforcement of formal and informal training, using consent mechanics does not become habit in the way that it needs to in order to change our behavior when we enter larp spaces. Because most of the players lived in the US, they largely came from a US culture that does not center consent as a dominant value. Larp creators must therefore ensure that a new culture is established for their games, formally and informally supported in a purposeful enculturation practice, to ensure that these practices come to life in embodied practice, rather than simply living in the pages of player handbooks and codes of conduct.